Improving Academic Writing Skills: Personal Perspective as an ESL Researcher

Published:

This is a cross-post of a post I wrote in medium. In this post I try to provide personal experience in improving academic writing skills as a non-native speaker of the English language.

If you’re struggling with academic writing as an English as a Second Language (ESL) researcher, you’re not alone. There is a wealth of advice available online, and even some pop up, unsolicited, in your mailbox. But much of it assumes that you already have some writing skills, such as the ability to write a short essay or letter. While this advice can be helpful in refining your writing to the formality and structure of academic writing, it may not be as useful if you’re still having trouble putting words together coherently or unsure about the proper usage of pronouns like “these,” “those,” “a,” and “the.” In this post, I’d like to share my own experience in improving my academic writing skills as an ESL researcher. While I’m not an expert on the subject, I hope that my personal perspective will be helpful to others in a similar position.

Photograph of a library. Photo by Calvinius

Thus, I’m not going to tell you to do this and that. Let’s face it, most often than not, generic advice does not work. If it did, there would not be many ‘Self-help’ and ‘How to’ books; If they’ve worked as advertised, I would have become a billionaire, sitting on the deck of a superyacht, basking in the turquoise waters and salty breeze of the Mediterranean, out for a coffee break from an advanced physical chemistry lab located in the basement. Believe of not, I have read my share of many ‘self-help’ books, including one on becoming rich, and thought hard, but did not grow that rich. Sorry, Napoleon Hill.

The Eastern Mediterranean’s small island off the coast of Fethiye, Turkey, is as beautiful as they say. The coffee was invigorating and the tour boat was not too shabby either.

I’m sharing this perspective in the hope that you may find bits and pieces that you, an aspiring postgraduate or Ph.D. student, like to adopt and tailor to your unique situation.

Academic writing isn’t a skill that most universities teach, so we often have to figure it out on our own. If you’re lucky, your advisor might help by suggesting revisions and providing concrete feedback to improve your writing. But let’s be real - most advisors don’t really care about our personal development. They just want us to align our goals with theirs. So they often don’t want to spend time helping us improve our writing skills. They’d rather have us do the experiments and draft the paper, while a more experienced Ph.D. student or postdoc takes care of the writing. That way, they can publish more papers and potentially get more funding. While it may be tempting to get your name on more papers, you’ll eventually realize that it’s much more fulfilling to do the whole process yourself, at least for one paper. It’s like baking muffins - even though you can buy them cheaper and faster, they taste so much better when you pick the blueberries, mix the ingredients, and bake them to your liking.

Lucky for me, my first advisor, Professor David Anderson, was one of the few willing to put in the time and energy to help students improve their writing skills. I still remember the first paper I sent him. I eagerly awaited his response, and was cautiously excited when he said it was good, but needed some work. But then he handed me back the paper, filled with red marks and questions, and I was devastated. After a few hours of recovery, I got to work on the revisions. And then another revision on top of the first revision. And even more revisions after that. It took over 10 revisions, but we finally submitted it.

If you’re lucky enough to have studied in an English-speaking country and had a helpful advisor, you probably had plenty of opportunities to improve your writing skills through classes, seminars, homework, and projects. But for those who don’t have that luxury, or even those who do but grew up speaking a different language with completely different grammatical rules, improving writing skills can be challenging. So, what has helped me improve my writing skills?

Writing

By writing, I mean writing anything - even just a few words or sentences - is a good start. They say that beginning is half the battle. When I do scientific research, I write down ideas that come to my mind in simple language and plan experiments on paper by writing out the major steps and reasoning. I also like to summarize papers I read by writing them down. Sometimes, when I’m upset or can’t sleep (like when a neighbor woke me up at midnight to ask about their cat), I write to myself to help me relax. Writing about why I’m upset can even help me fall asleep.

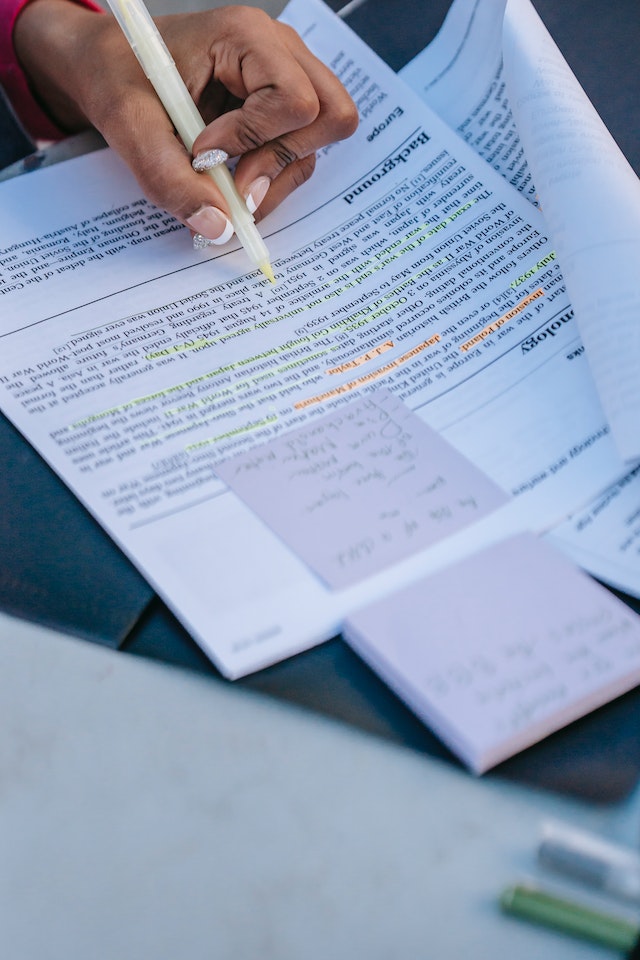

Reading

To become a good writer, one must read. I read a lot - before bed, on weekends and holidays, while waiting for the tram, and during my one hour commute. I have four modes of reading. The first is for fun, usually newspapers and books that are not scientific in content. The second is to stay up to date with my field of research, which is a quick mode that takes about 30 minutes to read a paper. The third is intensive and critical reading to find weak points and flawed arguments in a paper. To do this, I choose a good paper, read it carefully from beginning to end, and check references. Sometimes, I need to read other papers to fully understand the target paper. In the end, I write an extensive reading report including the main findings, unique approaches used by the authors, and any weak arguments or uncorroborated claims. This mode can take two to five hours for me, so I do it less frequently, usually one paper per month.

Photo by Keira Burton from Pexels.

Last but not least is reading aloud. In this mode, I read out a short and nicely written paper that is also easy to understand and read. These types of papers are easy to find in Physics Today and Physics. Science and Nature also have some good ones, especially among the Perspectives and Editorials. I read aloud a paper almost every day, in the early morning or after dinner, and it takes about 10 minutes. However, when I started this practice almost ten years ago, I used to read one paper out loud multiple times, sometimes on different days, to the point that I almost memorized it word by word. I think this practice helped me familiarize myself with the rhythm and grammar of the English language, even if subconsciously. These are my personal experiences and practices in academic writing, which is hard, takes time, and one gets better at it only by practicing.

But there is a niche: Scientific articles have a clear structure, starting with an introduction, then moving on to the experimental section, followed by results and discussions, and ending with a conclusion. This template helps organize ideas and arguments into sections. When we think about the process of writing an article, we realize that it starts with words, which are turned into sentences and paragraphs that are coherently connected. There is often a lot of rewriting, erasing, and rearranging of sentences and paragraphs involved in this process. Therefore, it may be helpful to start by organizing the structure of the article, then move on to writing down the words and connecting them into sentences. With regard to organizing ideas (or topics), an essay written by George Whitesides could be used as guidance.

To construct an effective outline for your writing, start by dividing your section into paragraphs and identifying the main theme of each paragraph. In the introduction, for example, the first paragraph should introduce the topic and describe the existing problems in the field. The second paragraph should describe how the community has attempted to solve these problems, and the third paragraph should outline your proposed solution.

When writing, it’s okay to focus on getting your ideas down first, without worrying about grammar or smooth transitions. Once you have something on paper, you can then work on editing and refining your writing. This includes checking your words, correcting grammar, and rearranging sentences to improve the flow of your writing, paragraph by paragraph.

We have finished one section. The process for writing the next section or any other sections is similar. In the end, we will have a rough draft from the introduction to the conclusion. I think it’s best to take a break from the first draft for a few days and come back to it with a fresh perspective. Then, work on it some more. Hopefully, the second draft will be more organized and clear. You can then send it to a more experienced person, like your advisor or a senior group member, to check the organization of the article. Once the structure is solid, you can focus on improving the language and readability.

So that’s it. Some of my practices may sound unorthodox, but they have been helpful for me. Please leave a comment and let me know what you think.

Some other useful writings on academic writing:

G. M. Whitesides (2004). “Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper” Advanced Materials, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200400767

Anne McNeil Group Advice: How to Write a Paper (2022). https://mcneilgroup.chem.lsa.umich.edu/resources/