Fundamental research is not superior to engineering

Published:

A scientist’s thoughts and reflections on the importance of applied research & engineering, and my journey of how I came to that realization.

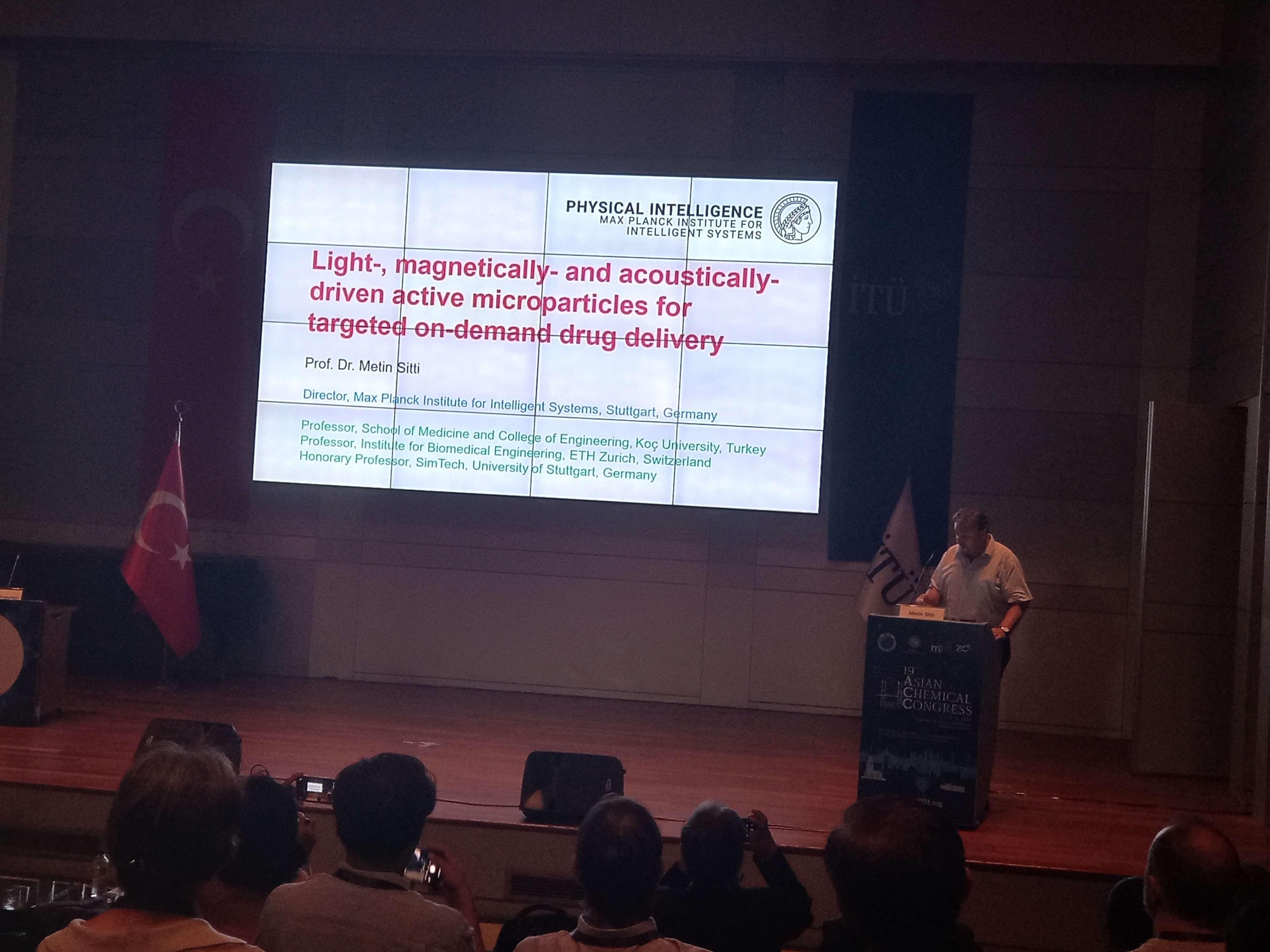

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to attend a conference where I gave a talk and listened to presentation of chemists and material scientists from around the world. Among the speakers, two stood out and left a lasting impression. Professor Metin Sitti from MPI discussed the biomedical application of microrobots, while Professor Kuzunari Domen from the University of Tokyo presented work on catalytic water splitting. Despite their focus on applied and engineering directions, the details involved in these research topics revealed an inseparable connection with fundamental research.

Prof. Metin Sitti from MPI Germany is delivering an invited talk at the Istanbul Tecknical University on July 15th 2023.

Prof. Metin Sitti from MPI Germany is delivering an invited talk at the Istanbul Tecknical University on July 15th 2023.

You see, as a young student, I used to view science and research through a narrow lens, dividing them into two distinct categories: basic (pure) research and applied research (engineering). In my mind, basic research, driven by curiosity and the pursuit of understanding “Why,” held a sacred position and I considered it to be superior. Scientists like Faraday and Einstein were like over-earthly saints, epitomizing the essence of scientific inquiry. On the other hand, engineering and applied research seemed less glamorous and were often overshadowed. I mostly blame this on science textbooks. In retrospect, I guess this skewed perception influenced my research direction, leading me to embrace the path of basic research during my master’s and Ph.D. studies.

For my master’s degree, I studied infrared spectroscopy of cold molecules and their reactions trapped in malleable solid hydrogen, probing the mysteries of molecular behavior at chilling temperatures of minus 271 degrees Celsius. Subsequently, for my Ph.D., I investigated the formation of nano and microclusters of simple molecules like water and formic acid at a bit ‘warmer’ temperatures of minus 196 degrees Celsius, employing infrared spectroscopy as my trusty guide. These research pursuits were mostly driven by curiosity while rarely considering applications. However, they provided valuable insights into molecular interactions at extreme conditions, with implications for phenomena like aerosol formation and infrared scattering in Earth’s atmosphere and beyond.

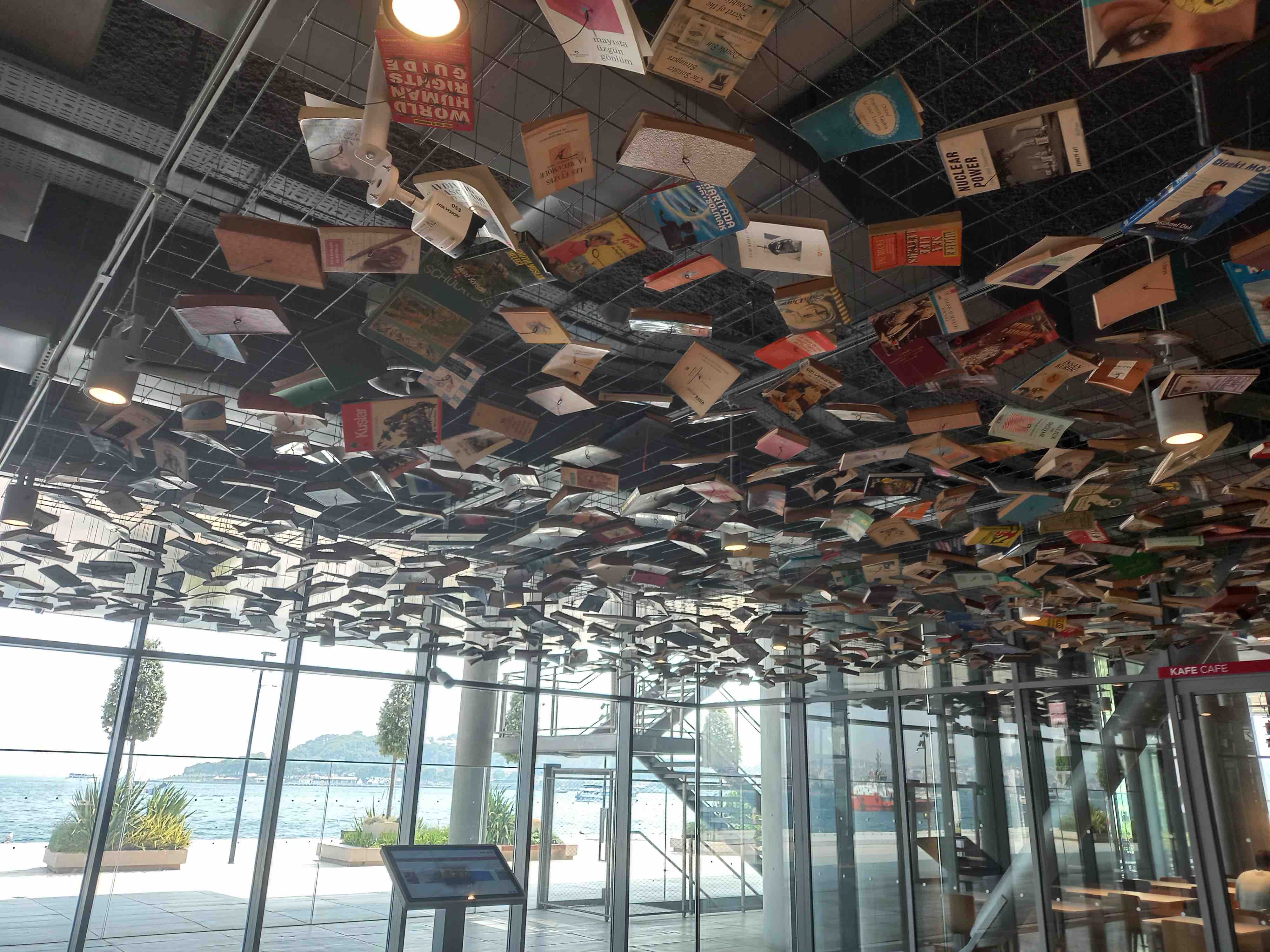

Inside the entrnace of the Istanbul Modern art gallery, from the Galata port side, July 2023.

Inside the entrnace of the Istanbul Modern art gallery, from the Galata port side, July 2023.

Everything changed when I started my postdoctoral work at Erciyes University. Here, I worked on two exciting research areas: surface-enhanced Raman scattering and superhydrophobic surfaces. While the former was somewhat familiar, the latter was an entirely new territory— I had never even heard of the word ‘superhydrophobicity’! These research domains challenged my preconceived notions and compelled me to see the value of applied research in solving real world problems.

Here, I explored preparing metal clusters on surfaces to facilitate the identification and measurement of trace amounts of target molecules, such as pesticides in water or proteins on microbial contaminated surfaces. Additionally, I worked on creating coatings that rendered surfaces highly repellent to water and, to some degree, dust and dirt. The applications were evident—these coatings could be employed on windows, solar panels, and more, providing clean surfaces for everyday applications.

As a novice in this field, I initially perceived applied research as primarily pragmatic, driven by trial and error to achieve specific desired end results without considering/understanding the details much. However, as I learned further, I realized that the boundary I had arbitrarily drawn between applied and basic research was far less rigid (even don’t exist) than I had assumed. Even in applied fields, understanding the “why” and “how” are critical aspect of inquiry. For example, one such study was about the impact of various parameters on the durability of a superhydrophobic coating prepared from silica nanoparticles and wax from carnauba palm tree. We found out the effect of various parameters comes to one simple fact: the self-assembly of silica nanoparticles and carnauba wax molecules. This work started to challenge my misconception, revealing how the two research domains could seamlessly intertwine.

As my perspective started to shake, I sought to learn more about others thought on the importance of basic research and engineering. One of the influential writings that shaped my new understanding was an essay by the renowned chemist George Whitesides, titled “Reinventing Chemistry. In this piece, he challenges the artificial distinction between pure and applied research, advocation for collaboration across fields to drive innovation . He wrote “In the new era, both academic and industrial chemistry (ideally with cooperation from government) would benefit from abandoning distinctions between science and engineering, between curiosity-driven understanding and solving hard problems, and between chemistry and other fields, from materials science to sociology.” I also found inspiration in a lecture by Richard Hamming called ‘You and Your Research’. He does not directly talks about pure research vs. applied, he never distinguishes them. This was refreshing to me, as his research involves both realms.

Oil painting on canvas, by Mustafa Orhan, March 2023 Kırklareli, Turkey.

Oil painting on canvas, by Mustafa Orhan, March 2023 Kırklareli, Turkey.

My journey of biases and transformation has taught me a valuable lesson. As researchers, we are susceptible to ill-informed believes and preconceived opinions. Embracing multiple fields and continuously learning enables us to challenge our beliefs and cultivate a more evidence-based worldview. By appreciating the symbiosis between basic and applied research, we can contribute meaningfully to the advancement of knowledge and provide practical solutions to real-world problems. As I progress in my research, I carry with me the understanding that the boundaries I perceive between different basic and engineering research domains are often artificial constructs, and true innovation arises from embracing the synergy between them. Of course, it is difficult for one person to be good at many fields, as each requires some distictive skills, then collaboration is the key to do really good and impactful research in the modern era.